Imagine yourself in a murky dungeon.

The only thing heavier than the air in this place is the pack on your back. You haven't eaten in days, and you can't remember when you last saw the sun. You think about your faithful little dog who joined you on your journey to retrieve the Amulet of Yendor.

And you think about how you had to eat his corpse after he was torn apart by orc zombies. —www.thegreatestgameyouwilleverplay.com

NetHack (1987) is a hard game to describe. Wikipedia describes it "open source single-player roguelike video game", which is true but unhelpful.

A line further in the article is only slightly better: "NetHack features turn-based, grid-based hack and slash and dungeon crawling gameplay, procedurally generated dungeons and treasure, and permadeath..."

These types of definitions, while accurate, don't do much to convey the game's essential flavor. In other words, what does it actually feel like to play?

For the new player, the experience can mostly be summed up in one word: pain. A few reasons for this:

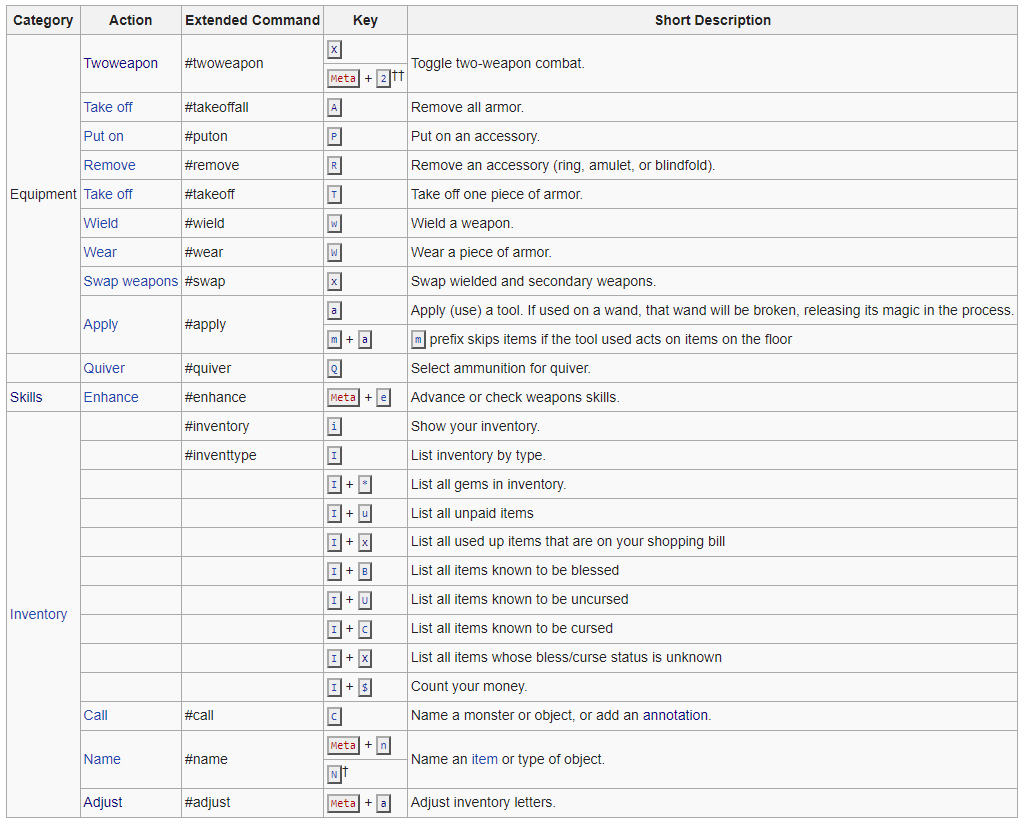

- NetHack is visually opaque. The player character is an

@sign. Their pet kitten is anf(feline), not to be confused withF(fungus.)hsometimes represents a dwarf, but it can also represent a mind flayer. Confusion abounds. - NetHack's controls are difficult to learn. Nearly every button on the keyboard is mapped to an action, and some to multiple. The control scheme seems to take a similar philosophy to

vim: minimum keystrokes per action at any cost. - NetHack is brutally difficult. One player describes trying and failing to beat it without spoilers for 24 years. Another player claims that they were able to win spoiler-free after 1700 games, although this is still contested.

- NetHack is for nerds.

With these seeming deficiencies, what is it that causes gamers to stomach (and even grow to love) the game? What inspires people to pen the pages-long dramatizations of their quest runs known as YAAPs (Yet Another Ascension Post) and YASDs (Yet Another Stupid Death)? Why would a random internet magazine (not even a gaming publication) run an article thirteen years after the game's release proclaiming it to be "the best game of all time"?

As someone with a few wins under my belt, I feel qualified to take a stab at answering those questions.

NetHack is visually opaque

Just as a mathematician seeks elegant expressions over fuzzy generalities, NetHack eschews graphics in favor of perfectly crafted, well-defined ASCII characters. While other games are dated by their interfaces, NetHack is preserved in ascetic purity. —NetHackWiki

Although the above quote leans a bit toward the dramatic, it does have some truth to it: NetHack's abstraction is one of its greatest strengths.

But to me, it's less about "ascetic purity" than the ultimate effect on the gameplay experience: the symbolic nature of the game world requires interpretation—the player has to "meet the game halfway", so to speak, using imagination rather than relying on visuals to bring the story to life.

To the practiced player, the sudden appearance of an uppercase X can be the scariest thing in the world: the metallivoric xorn, with its claws, its devastating bite, and the ability to phase through walls to follow the player.

And a lowercase c becomes a fearsome cockatrice, which has the power to turn the hero into stone at a touch—and retains that ability even as a corpse.

In some ways, playing NetHack is more like reading an interactive novel than playing a video game. Gameplay is the pen with which the player composes their story—one with its own heroic arcs: rising actions, climaxes, and denouements, all the way to a glorious or untimely end.

NetHack's controls are difficult to learn

The International Roguelike Development Conference in 2008 codifies "complexity" as a crucial factor of roguelikes:

[A roguelike] has enough complexity to allow several solutions to common

goals. This is obtained by providing enough item/monster and item/item

interactions and is strongly connected to having just one mode.

NetHack goes beyond this definition, achieving complexity through not only a vast dictionary of hundreds of items and monsters (let's call them "nouns") but also dozens of verbs, actions the player may perform. It is this preponderance of verbs that makes the controls of the game so unwieldy at first glance.

A non-exhaustive list includes: eating, drinking, throwing, kicking, jumping, reading, zapping, engraving, un-trapping, wearing, wielding, enhancing, invoking, rubbing, offering, tipping, opening and closing doors, forcing locks, and dipping things into other things.

If the game is a story the player is writing, NetHack gives the player a rich vocabulary to write with.

Additionally, non-player actors have access to many of the same verbs as the player character, resulting in a combinatorial explosion of emergent gameplay. Here's a miscellaneous list of situations that can happen:

- Nymphs (a type of humanoid enemy) will attempt to seduce your player to relieve them of their clothing. If they happen to steal a cloak of invisibility, they will gladly equip it and rob you blind while you swing your weapon at empty air.

- "I got bitten by a wererat, and I transformed into one right in the middle of a fight with an ogre. Overloaded, I managed to grab only my sword and dashed away. From a distance, I watched in disbelief as the bastard began equipping my stuff and using my healing potions! Just as he finished, I reverted back to human form. So there I was, standing naked, clutching my sword in front of him. And what's a newbie to do in a situation like this? Attack!!! Dead."

- Pets will pick up items randomly, including unpaid-for items in shops. Magic whistles can be used to teleport pets to the player character from any distance. The application of these two facts is left as an exercise to the reader.

NetHack is brutally difficult

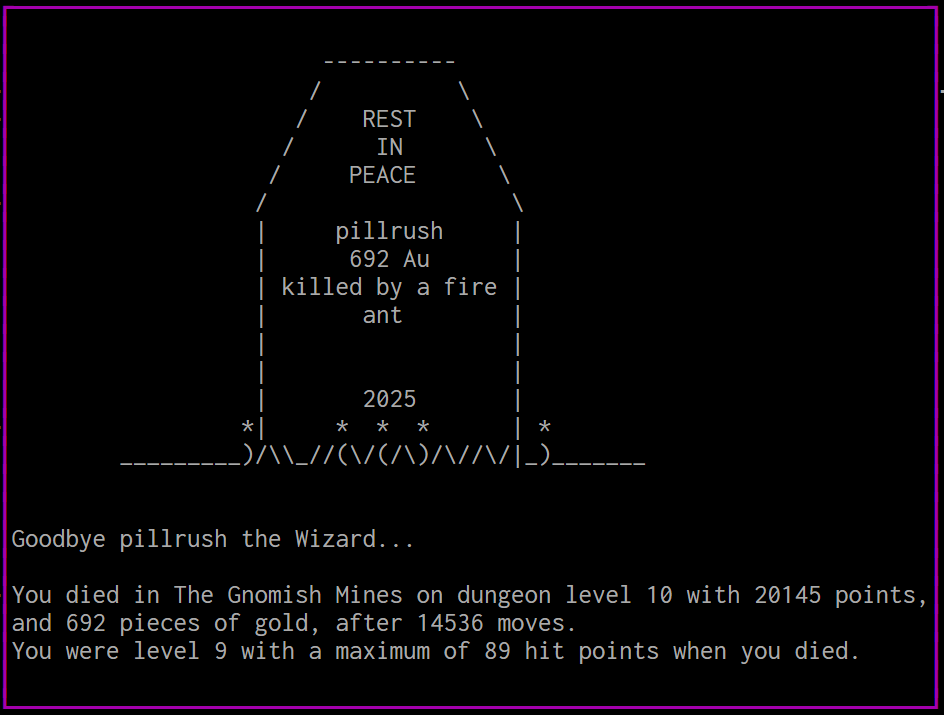

NetHack is unforgiving: if you die, you stay dead. There is no save-and-reload crutch here. Put simply, NetHack is a harsh mistress, whose respect you must earn. In time, you learn to respect it back. —NetHackWiki

NetHack does not care about your player experience. How else can we explain a game in which each run lasts dozens of hours being littered with opportunities for instadeath—all the way up to the very last screen?

Although that in itself might be somewhat appealing to those with a masochistic bent, the game is not intentionally cruel—at least not in the vein of games like I Wanna Be The Guy that delight in baiting the player into intentional traps. NetHack is neutral. It has few guardrails. It allows you to shoot yourself in the own foot in a hundred different ways. Playing it requires "rigor", for lack of a better word.

In fact, NetHack is unforgiving in much the same way as early UNIX distros, which would happily allow you to rm -rf / and blow yourself up. It shares a lot of DNA with that early computing ethos. As the wiki states, "The programmer is drawn to NetHack as an extension of the operating system. Its culture is deeply intertwined with that of the Unix systems, and indeed is a staple fixture on any good Unix system - a known quantity, ageless, familiar, and soothing; whatever hairy command-line tasks are required, nethack(6) is always there."

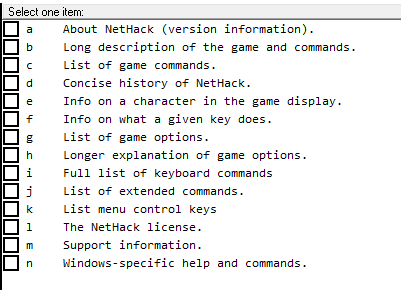

Perhaps the strongest evidence for this intertwined culture is the fact that NetHack completely lacks a tutorial but instead ships with documentation.

NetHack was one of the first games to be developed via remote collaboration (the "net" in its name comes not from the word "Internet" but from USENET, a early predecessor.) Since only nerds had access to computers at the time, nerds were the ones who developed Nethack. They were interested in building systems full of complexity, challenge, and Lord of the Rings references. Through four decades of development under the hands of dozens of contributors, the game grew more and more intricate, more and more convoluted.

In some respects, therefore, NetHack's difficulty reflects not a specific design philosophy but rather the circumstances of its creation. There is simply so much content, so many interactions, and so many random gotchas that it's almost impossible for one person to remember it all.

All this to say that I recommend using the wiki. It makes things a lot easier and more enjoyable.

NetHack is for nerds

livecat = rn2(2) ? makemon(&mons[PM_HOUSECAT], box->ox, box->oy, NO_MINVENT) : 0; —observe_quantum_cat, pickup.c, Source:NetHack_3.6.1

I have no rebuttal to this. NetHack is deeply nerdy. A few in-game Easter eggs:

- On attempting to dip a potion into itself: "This is a potion bottle, not a Klein Bottle!"

- Breaking a gemstone while hallucinating: "Oh wow, man: Fractals!"

- Randomized scroll name "JUYED AWK YACC" is a reference to the Unix tools ed(1), awk(1), yacc(1).

I don't think this nerdiness is a downside though.

Click friend and enter

No graphics, no sound, no razzle-dazzle—but NetHack is still one of the finest gaming experiences the computing world has to offer. —Salon

If you can get past the interface, the controls, and the difficulty of NetHack, ample rewards await—in richness of story, interactivity, and depth of gameplay. Unfortunately, the intricacies of actual gameplay are out of scope for this post. I will only gesture vaguely in the direction of the official site (where the game can be downloaded), NAO (where the game can be played in-browser) and the wiki (absolutely essential unless you hate yourself.)

Obesa Cantavit.